The other day, Steve Garro of Coconino Cycles posted an image to his Facebook wall that got a bit of attention. This probably isn’t a new image for some people to see but it got a lot of attention. Specifically, it got my attention. I was in the mood to really think about some bike design and this little gem landed right in my lap. People were wondering what the geometry of the bike was and I did too. The game was on.

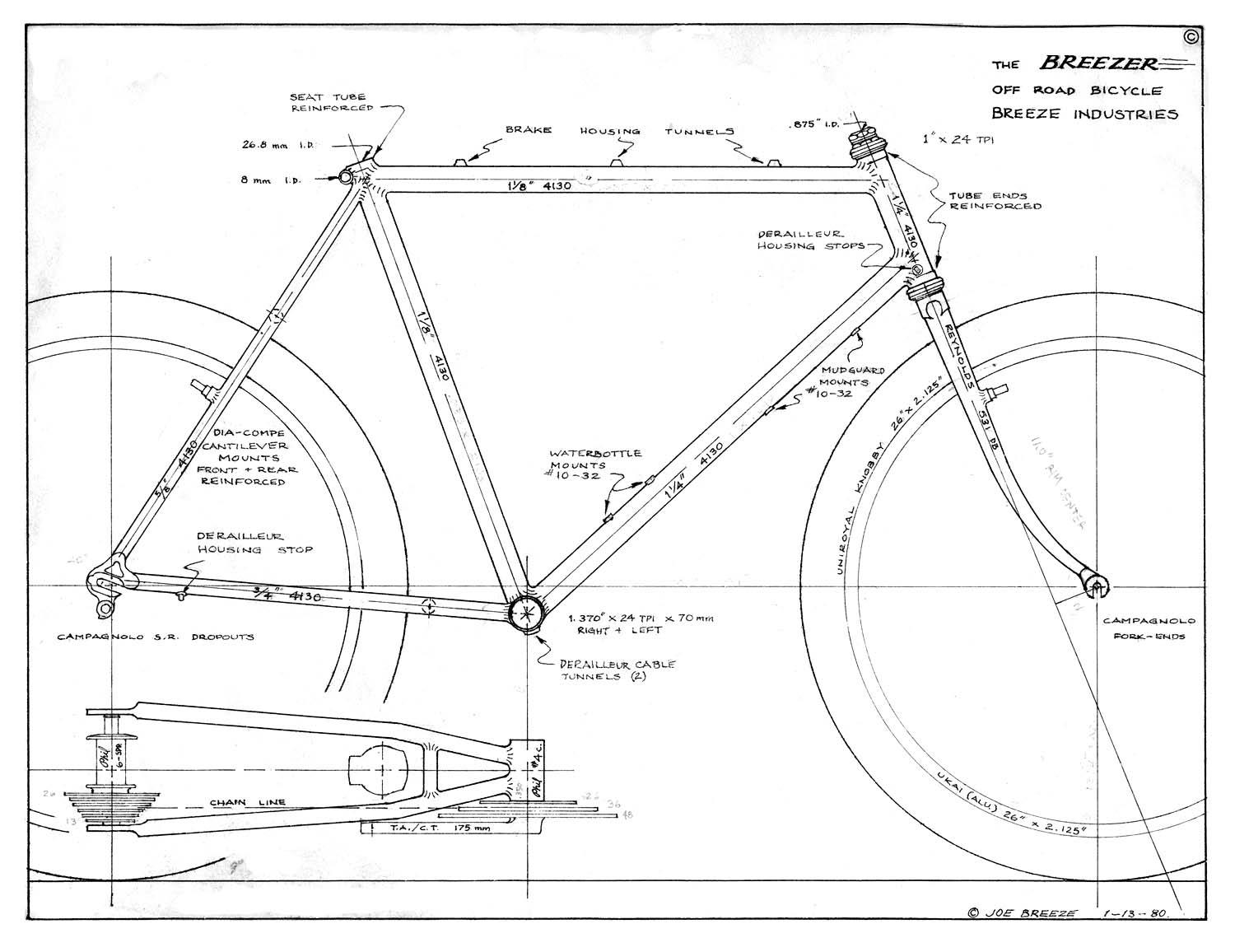

It’s a print of 1980-81 Breezer Off Road Bicycle, Series 2. As some may know, the 1977 JBX1 Breezer was the first purpose build mountain bike frame and it was designed and built in my town of Fairfax, CA by Joe Breeze. It was followed later that year by the 1977 Breezer Series 1 (9 produced). The series 2 (25 produced) is effectively the same geometry as the Series 1 but it uses a different construction design.

Joe Breeze is quite famous in the bicycle world and is a member of the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame. On top of all that, he’s a very cool guy.

The print that Steve had posted shows some of the elements of the design but no geometry. After tracing the image in cad and chasing details around, I decided to go to the source to get exactly the right numbers.

I sent Joe an email and we entered into a discussion about the bike. Here’s an excerpt:

“Hi Pete,

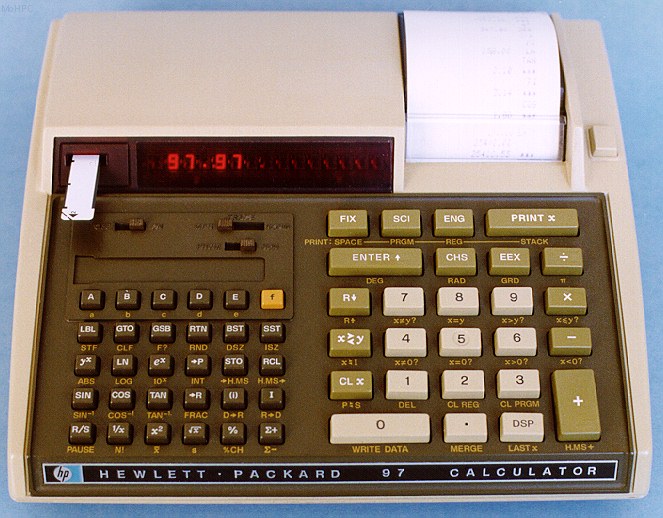

Attached is a PDF I made today with Breezer Series 2 dimensions from 1980. I eventually referred to my 1980 frame program data. My father and I worked out this program in 1975. He enjoyed math and loved to derive formulas for solving the smallest problems on up to intergalactic mechanics. He was always buying the latest calculator, slide rules and adding machines, then later, an HP-35, then HP-45, then finally an HP-97. He died in 1980 and missed out on the future he was looking forward to so much. Didn’t quite make it to the personal computer with monitor era.

The HP-97 had programmable cards that could be wheeled through the machine. Numbers would be crunched and the output would be typed out on heat-sensitive paper. I used our program up until the early 1990s when a friend, Adam, helped me update it for my CAD program.

The original program was devised for road bikes, so the fork length is arrived at through the front brake dimensions. My new program forgoes this and the fork length (measured on the steering axis) is used. Back in the 1970s and 80s I measured forks from the axle center to crown seat at the FRONT of the crown. That was the easiest way to measure a real fork after all. On the drawing, you will see there’s no tidy number for fork length, no matter how you measure it.

On my PDF you will see bolded and unbolded numbers. The bolded numbers represent what are essentially the input dimensions for the HP-97 frame program. You can see how the height of the bottom of the head tube is determined by rim diameter, brake reach, brake offset, brake drop, and headset width. BTW, I used .570” for the latter, not .550”. A dimension of 1.3 inches was assigned to the distance from HT base to the HT/DT intersection. This is another carry over from road bikes, from lug dimensions. My new program avoids this.

Anyway, I hope this is useful.

Best, Joe”

Something that is so interesting about this is that I was just at the Trips for Kids ‘Meet the Mt. Bike Pioneers‘ fundraiser in San Rafael (02/10/13). Many of the famous names in early mountain bike development were there. One special guest was Chris Chance. I worked for Chris at Fat City Cycles a long time ago. I was sitting with him having a burger when Joe Breeze arrived and sat down with us. We were talking about this post. It turned out that Chris had used the same HP97 calculation technique for all of his early bikes as well. This is a fascinating fact that at least two of the most famous names in American bicycle design didn’t produce designs on paper, rather, parametric input for calculation of related geometry.

The materials:

HT = Ø1-1/4” with rings, 4130

DT = Ø1-1/4” x .049”, 4130

ST = Ø1-1/8” x .035” with upper ring, 4130

TT = Ø1-1/8” x .035”, 4130

CS = Ø3/4” x .049”, 4130

SS = Ø5/8” x .035”, 4130

Bridges = Ø5/8” x .035”, 4130

BB = 1-1/2” x .083”, 4130? or 1020

Steerer = Reynolds 16/13 ga

Blades = Reynolds 21/18 ga?

Breeze billet crown = 1” x 1-1/4” drilled hollow, 1020

Campagnolo dropouts, short

HS = 30.2/26.4mm Campagnolo steel

I reconstructed that print in BikeCad so as to have a clearer understanding of the design. Note the corrected fork length that produces correct numbers. It’s nice that we have conventions now that make this whole process quite a bit easier.

I asked Joe; “Was Richey building bikes before you did the Series 2? Was anybody?” Of course, I knew that he was building bikes, I was talking about mountain bikes.

“Tom Ritchey built his first frame in 1972. I met him and his dad while at the San Rafael Criterium under the arches at the Civic Center. Tom was 15 years old and I was 18. I had ridden through Europe the summer before and met Cino Cinelli at his Milan factory. Like meeting god. At Presto, an Amsterdam bike shop, I almost bought a Reynolds tube set. At that time there were very few frame builders in the US. In the Bay Area, I knew of Albert Eisentraut. Eisentraut taught me how to build frames in 1974. After building a few custom road racing frames under the the “Joe Breeze” name, I built Breezer #1, my first mountain bike, in 1977. Nine more Breezers followed by June the following year. Ritchey built his first mountain bikes in 1979 after I showed him Breezer #1. I hooked up Tom with Gary Fisher and that led to Fisher partnering with Charlie Kelly to form MountainBikes, the first business focused entirely on the subject. For years, Ritchey supplied MTB frames to them. The downtube decal read, “Ritchey MountainBikes”. Ritchey parted ways with Fisher in 1984. Kelly had split with Fisher the year before.”

In response to questions about what drove the geometry of the bike, Joe answers:

“Breezer Series 1 geometry:

From 1973 I tried out every ballooner available. The best was the Schwinn DX model from 1935 to 1944. These were the bikes that we in Marin referred to as “Schwinn Excelsiors.” The Schwinn Excelsior X was Schwinn’s top model of the balloon-tire “paperboy” bike genre. Many a klunker was built with these old frames. But the Schwinn “Excelsior” bikes we rode were not all emblazoned such. There were many other Schwinn models sporting their characteristic hip-stayed, double-top-tube design. In fact, Schwinn built bikes for many outside brands, such as B. F. Goodrich, like my featherhead and blue ‘41.

I measured up my ‘41 and applied the basic geometry to Breezer #1 with 67.5 head, 70 seat angles. On the other Series 1 bikes I steepened the head to 68 degrees. One of the earlier bikes I had ridden, my maroon ‘45 Schwinn, had a 70 degree head. I had liked the steering, but it was not my regular ride because its BB was an inch lower and hitting roots made it a liability. But it did influence me to go steeper. It wasn’t until Breezer Series 3 that I used a 70-degree head. That was still well before it was the norm. So-called “Marin geometry” refers to Fishers and Ritchey bikes, who hung onto slack heads and short top tubes for some time.

Speaking of head tube angle, perhaps you saw my 1988 experimental frame with 78-degree head. For years mountain bike heads were getting steeper and I wanted to get a glimpse of how far it might go. My 88X had seat, HB, BB and front axle and trail all exactly like my late ‘80s 70°/72° American Breezers. Only how I got from axle to HB was altered: 78 head with zero offset fork and stem and a long top tube. Once I got used to the quicker handling (less lean for a given radius turn) I could hang with the boys down anything. But getting back on other bikes afterwards was an ugly experience—they felt like slugs!

For my 1990s spear-point Breezers I went with 71 degrees for 1991 and 92, then to 71.5 degrees by 1993. I still tend to use steeper angles than most builders. I like the crisper feel. It gives a fun ride. I suppose rider reflexes need to be better honed, but these sport bikes are for riders on the gas. My road bikes like the Breezer Venturi are like that too, sporting 74 head (versus 73 norm) for a mid-size frame. 73 is fine for a multi-day bike, but there should be plenty of room for a day rocket.”

Joe Put a bunch more work into this project and sent me the following:

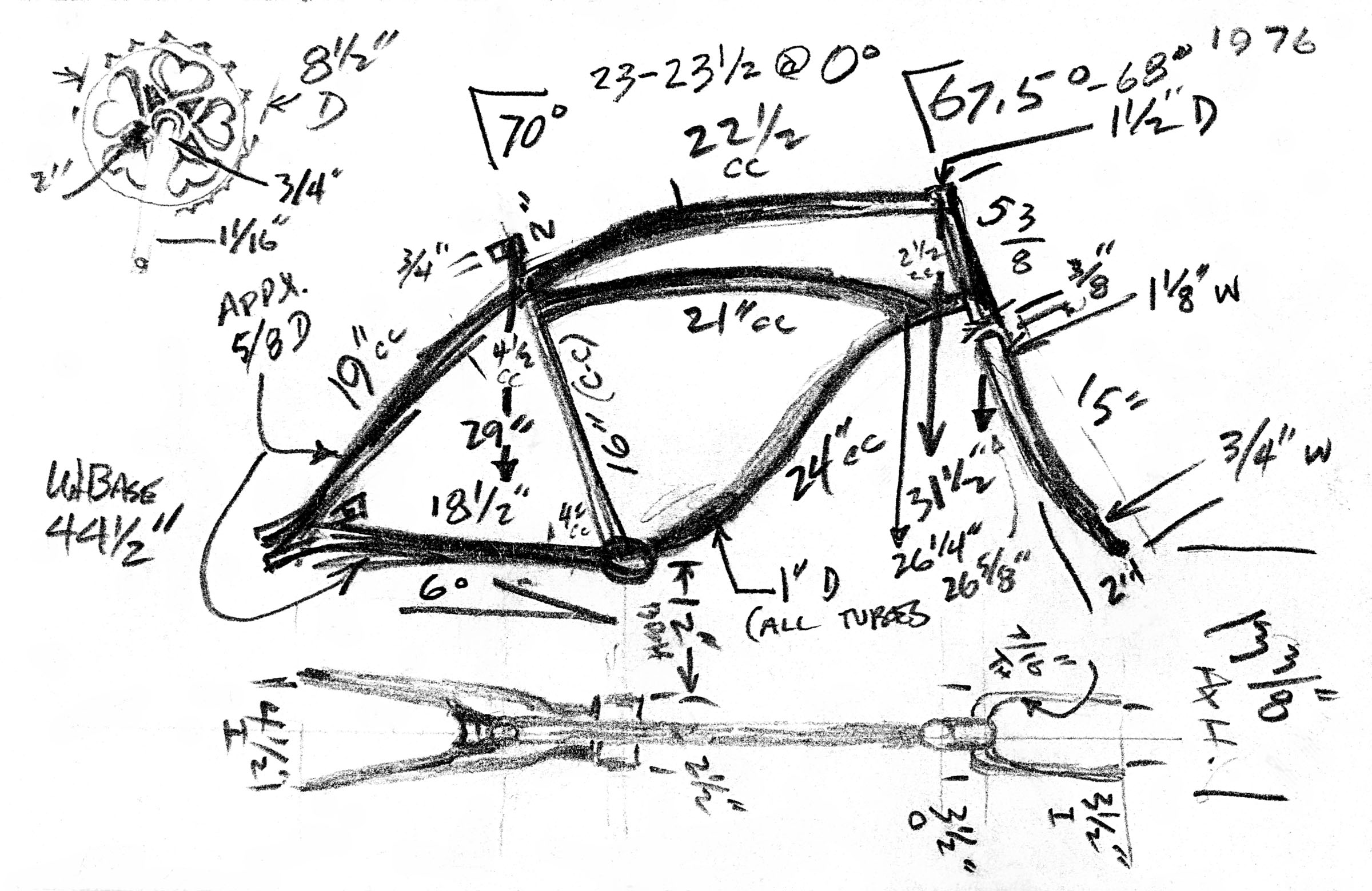

Here’s a drawing of Breezer #1, the prototype for Series 1. You can see how it compares to my 1976 sketch of my BF Goodrich. Maybe you’ve seen my drawing of Breezer #1 titled “Custom Cruiser” from May 1977. That was a conceptual drawing for the bike. By the time I built JBX1 in September 1977, there were a few changes made. For one, Lee Michaels*, wanted to run a one-speed setup and convinced me to use track tips on the rear. My plans were to make all ten bikes the same.

The reverse sloping TT: You will see that the HT are the Schwinn and Breezer were essentially the same, about 5.3 inches. This was so it could be replaced with a vintage Schwinn fork if need be. There few suitable modern forks available at the time. Most everyone interested in a Breezer was tall. Tall people were tired of bending far-extended seat posts on their klunkers. The longest available quality seatposts at the time were only 180mm long (nowadays they are 350-400mm), so I made the seat tube 4 inches longer than the Schwinns had.

The twin laterals running from the head tube to the rear tips were to had more lateral rigidity as these frames were over four inches longer than the road bike frames I was making. Not long after making the Series 1 Breezers, I did the math and determined that I could achieve the same rigidity and strength and save 3/4 lb by putting just some of the weight of the laterals into a bigger downtube and slightly thicker chainstays. Eleven fewer welds was an attraction too. “Strength in unity” has been part of the Breezer ethos ever since.

JBX1 forks: I hadn’t been able to find suitably strong fork blades, so went with track sprint blades used fork braces similar to what our old Schwinn “Excelsior” bikes had. I even made the “mouse ear” spring plate at the top. I learned that Cook Brothers was offering 26” BMX forks in SoCal. For Series 1 production I had them make a shorter version form me. I brazed on bosses to the dropouts for additional strength. These forks, with their straight, full-length 1” diameter blades were inordinately harsh. That got me going on the uni-crown fork design with the same BMX top, but with curved and tapered blades. But that’s another story….

*–If the name Lee Michaels sounds familiar, he is indeed THE Lee Michaels of the 1970s hit, “Do You Know What I Mean.” Check it out on iTunes. Brings me right back to the moment. Listening to it right now. 🙂 Early mountain bike photographer Larry Cragg was owner of Prune Music in Mill Valley, a hangout for musicians. That’s where I met Lee. Craig Chaquico of the Jefferson Starship was a client of Prune and had ordered a Series 1 Breezer. Unfortunately, on a German Tour, Grace Slick found herself too ill to perform. The fans rioted and set fire to the stage destroying the band’s equipment. As a result Craig found funds too tight to buy the Breezer. Terry Haggerty, of the Sons of Champlin, did buy one of those first Breezers, as did Larry Cragg. The other music connection is Repack impresario, Charlie Kelly, roadie for the Sons.”

I hope this is useful for folks out there. Extra special thanks to Joe for going above and beyond contributing to this post.

Edit 1/7/2014 – BTW: Here’s a nice photo essay on Breezer #11 in The Pros Closet to give you an actual image of the bike in question.