Here we are, well into 2020. The bike industry has just two products to sell: ebikes and all-road bikes. Nothing else matters. Those are the money makers and all that folks are really paying attention to. Everybody is trying to stake a claim.

On February 15th, I saw a few images on someone’s Instagram that sparked this post. It made me laugh (a little) but mostly made me sad. Cartoon sketches of imaginary bikes are something anyone can produce and don’t require any nuance. I really don’t like the Instagram format and how it stifles elaborated disclosure or discussion. Sometimes, just a few words are worth a thousand photos.

Over the past few years, much has been discussed about these “all-road bike” things in the cycling world. Mostly from people that aren’t very experienced in putting bicycles together, especially by those that don’t ride in dirt. It’s amazing that a bike such as the Open-U.P., in size large, with its front center of 604mm, seat tube length of 560mm, and 27.2mm seat tube bore, can be considered anything but a criterium bike. To call the U.P. an all-road bike is complete buffoonery. It’s painful to see people dig themselves into holes explaining this garbage.

What are we to do?

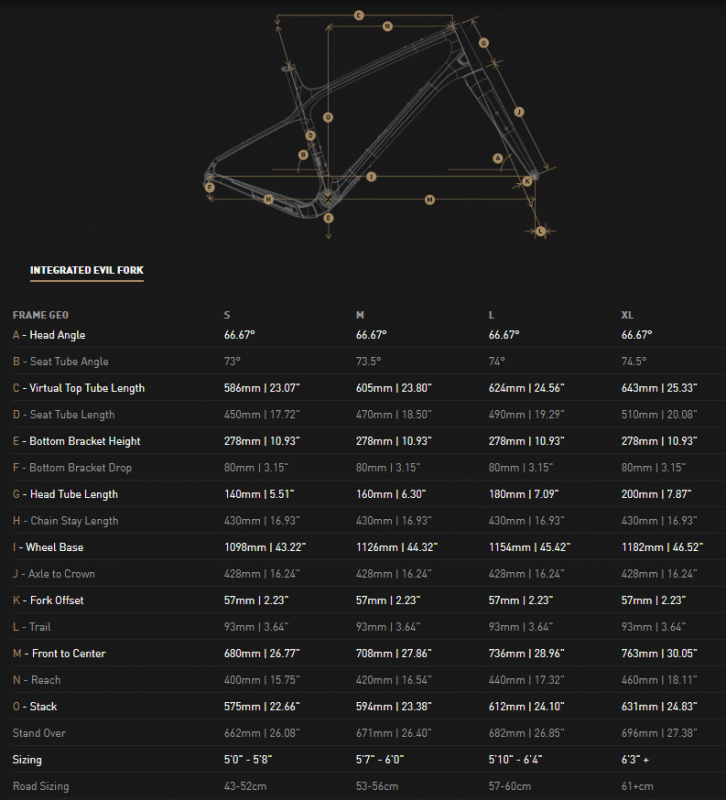

Recently, I’ve been recommending the Evil CH to folks looking for an all-road bike that isn’t an antique or absolutely terrible. I don’t know of another mass market bike that has made a serious attempt at selling a modern all-road bike. For most people it’s the clear choice, all but the committed roadie. Basically, this is the only bike in town…other than mine.

I don’t think that the Evil CH is the pinnacle of design at the moment. It’s got problems that folks like me were contending with many years ago and it suffers by choices made that could have been much better with a bit of experience in the genre. Still, compared to everything else out there, it gets more right than it does wrong and it is going to be the best mass market choice for most folks looking to take a drop bar bike into the dirt.

What are we talking about?

Often, we hear or read the comment that all-road bikes are becoming equivalent to 1990s rigid bikes. It’s simply not true and utterly uninformed. Aside from the obvious technical improvements in the components, there are several important details that exemplify a well designed all-road bike.

- The bike uses narrow Q145 road cranks. All-road rides are long and are meant to take a full day of pedalling. A bike with a Q177 crank is a painful joke if you are spinning your legs all day. Few people in major road grand tours are looking for wider cranks because that’s not what we want when pedalling. They also reduce cornering clearance.

- The bike has provisions for a dropper seatpost. This means a shorter seat tube and a 30.9 mm (or better, 31.6 mm) seat tube bore. A 150mm stroke minimum dropper post is fit to the bike. People arguing this don’t understand what a dropper post does. People arguing this have very little experience.

- Because the bike has provisions for a dropper post, the geometry should be designed around a zero offset seatpost and that the rider doesn’t have to maneuver a high saddle. Fitting a bike with a 30mm setback will wreak havoc when the post is swapped out for a dropper.

- A large front chainwheel can be fit for flatter (think Kanza) rides. An all-road bike needs to have a full selection of gearing. Limited to less than 42t isn’t legitimate for a full range of uses.

- A 50mm front tire can be used. A rear tire should get up to at least 46mm (see #6) but the front should have room for at least a 50mm tire. This is what is necessary when tracks are rough and need to be smoothed out. This is the primary suspension and grip and needs to be an option.

- Provisions for front shifting (46mm rear tire max). In general, all-road requires gearing far greater than 500%. To really ride dirt to the top of a hill, and pavement down the hill, you need some real range. A dedicated 1x setup limits you to 500% or less (currently). If you are going to take this hit, know that you are and get some improved tire clearance from it.

- The frame has flexural properties in between that of a road bike and a hardtail mountain bike. More toward the road bike. This is to ensure rider comfort in the road and dirt segments, not maximizing control in rock gardens or durability hucking drops. Since the tire volume is low, this frame flex helps the bike track better when in dirt. This also helps to make the frame lighter.

- The frame will takes proper 622 ETRTO wheels and tires with significant specified clearance. A 584 ETRTO is not a legitimate size in this category of bike and is only used by lazy designers and ignorant marketers. If World Cup XC, DH, and Enduro riders are almost universally riding 622 rims, you should be also.

- A maximized front center that allows for higher speeds and greater control in the dirt. This is the real killer as most bikes marketed as all-road bikes are dangerously short. Forward geometry principles still apply to all road bikes.

- 110mm front axle with. This is where the market will end up. Consumers just need to be fully milked first, Obviously.

- Cheap aluminum. Now is a terrible time to invest in a bicycle frame, either in all-road or mountain. The way we do things is changing rapidly. Even if you were to get a modern bike now, it would be hopelessly dated in just 2 years (see flat mount mtb and 110×12, and bi-plane bars). Buying fancy carbon right now is a foolish move.

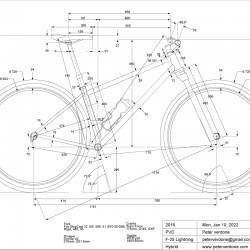

My earlier work in this arena were the 2013 PVD Light Cycle, 2013 PVD Raider (terrible failure) and 2008 PVD Skinny Puppy. The Light Cycle had seen some changes over time and was shown with a dropper post in 2015 in the Gamechangerz article. At the time, the Light Cycle was one of the nicest all-road bikes that I had known but it was just prior to the Red Five era of PVD development (Gen-11, Lightning, Bird of Prey, Airspeeder) which has had a ripple effect on all of my designs.

Conceived, not as a cartoon on a napkin, but in my workshop in early 2016, I produced the 2016 PVD F-35 Lightning to set a new standard in the hybrid framework. How much flexibility could be designed into a narrow gauge bike? In early 2018, the bike received a new Baron-type fork., mostly because I had sold off both the other forks that I had for it and wanted a proper 110mm spaced fork with cleaner looks and improved flex. The bike stands out even now.

I bring this up now because while recovering from injury, I’ve been cleaning my basement and sorting bikes out. I have my “A” bikes but found a way to get two “B” bikes back from parts on hand, with a few minor purchases. The Lightning was the last to get put back together. Since my 2019 Airspeeder is my A all-road bike and takes care of general use, I rejiggered this to be more of a rough surface all-road bike. It has higher volume tires to smooth out dirt road or go faster on trail. It also has provision for a 100mm suspension fork. It’s a pretty nice B/C bike.

Still, the bike has Q145 cranks and a 42t chainwheel although it could go up to 50t for rough urban (Boston/NYC/Chicago) use. For riding in Marin (read lots of big dirt climbs), the bike will probably be used with a 36t ring most often. It’s set up for covering ground quickly but can still smooth the ground out.

Obviously, were I to be designing this bike today, it would have a significantly longer front center and make use of PVD fabricated handlebars. But this geometry still holds up as this bike can use commercially-available flat or drop bars, something my current bikes won’t do.

What makes this 4 year old bike different than the Evil CH?

- It has a 34mm longer front center. Not as long as the Airspeeder, which is 49mm longer. Which I’d make 10-20mm longer if I were to go back again. This is a massive difference in capabilty when using the bike.

- It has a 90mm shorter seat tube compared to the (L) CH tube (490mm). I generally won’t even look at a frame that has anything longer than 450mm. In the era of 185-210mm dropper posts, that space is important. On a CH, I’d be forced to use a 125mm post which would sketch me out entirely. I don’t like excuses built into my bikes.

- Massive tire clearance. Running a 622-57 rear tire on some rides is fan choice. Tracks can be rough and loose. Clearance is 622-61mm tire in the front if it’s really banging.

- The Lightning has an extra 10mm of bottom bracket height than the CH. Granted, I love a very low bottom bracket as much as the next guy but if you plan on covering ground that does have rocks on it, a little more room really helps. The CH is very low.

- 110mm spaced front wheel. Strengf.

- The elephant in the room, the Lightning can run a 100mm travel suspension fork. I don’t recommend that, but the option exists. One thing I’ve learned over the years, it is hard to predict how a bicycle will need to be assembled 5-6 years after it’s been designed and produced.

The number one problem for anyone designing all-road bikes today is the lack of bi-plane handlebars in the aftermarket. This one item holds back a huge amount of geometry choices and development if drop bars are to be an option for a bike. I spoke about this years ago. We need this to change. Roadies are too ignorant to understand.

****

It happened that just today, coming back from a slow and steady loop around Tamarancho on the Spitfire, I came across a free pile that had some bike stuff in it. At the bottom of the bin was a pair of bar ends. This cracked me up. I’ve been riding bicycles seriously since 1989. I have never, ever, ever had bar ends on any of my bikes…until today. Fate chose me.

There is one reason to use drop bars on a bicycle, aerodynamics. This is crucial for real road riding. Riders will spend hours riding into a headwind on very smooth surfaces, often attempting high speeds. All-road is a lot slower and control gets more critical. Most of the time, the resulting gain from aerodynamics is minimal. Still,on road sections, aerodynamics can help. A few more hand positions would be nice for all day use.

I put the bar ends on the Lightning. Set inboard. I keep all the control of the wider bars but can get myself a little more out of the wind if needed. They aren’t much of a safety hazard in trees which is important for faster singletrackers. Then the ends can be utilized when there will be a gain from that, just like the center grips on my Airspeeder bars are often used to shape the wind around me on road.

I’ll probably be swapping out to a 90×0 stem once I find it. A little more test riding will dial things in. I think the bars are a little high as shown in my details here. It takes some time to get a setup just right.

The current plan for this bike is that Ronen is going to do some fit and configuration testing for a SF/Headlands/Tam bike that we might construct. Something that can be ridden from his apartment near Golden Gate Park, across the bridge, and over dirt toward the top of Tam. It will certainly have smaller tires on it for that and probably a 36t chainring. Maybe a 38t as he is young and quite strong. I’m thinking that the bar ends will be moved to between the grip and pertch to meet his preference but we will sort that as testing starts. I’m sure that the a bike constructed from this testing will look much like the Airspeeder with some refinements for his specific needs. Ski season needs to end first as that is his #1 priority right now.

I like that my work of four years ago stands up against what is in the market. Reconfiguring bikes over time tells how well designs hold up. I see again what I did, what worked, what didn’t. I do this a few times each year to keep my fleet fresh and relevant, and also usable as loaners. This bike is doing ok. It’s probably got another year left in it but that’s pretty good. Evil almost.